by Janet Kent

This summer, I went with my mother to visit the cemetery where her parents and other relatives are buried, less than a mile from the one room shack where she and her three siblings grew up. My grandmother, Elizabeth Pitman Buchanan, died of tuberculosis when my mother was 9 years old—and even as she approaches ¾ of a century, this is still the defining moment in my mother’s life. She, like many children who lose one of their parents when they are young, has few memories of my grandmother. One important memory came to light in the past year.

My mother on my grandmother’s knee, 1940.

My mom grew up in an Appalachian holler much like the one I live in now. Her family was poor—the kind of poor that is hard for many Americans to imagine. Though the Depression was technically over, the hill folk of the Appalachian mountains would not recover for decades. Fortunately, my mother’s family had a little piece of land on which to grow food so they seldom went hungry. They grew most of their food and put enough by to eat throughout the winter. Every inch of their yard was devoted to this purpose except for one garden bed. In this bed, my grandmother planted bulbs and seeds of flowers. She especially prized those that bloomed in June, for that was the annual Decoration Day at the cemetery where her relatives were interred. Every year, she and the other women in her community traded seeds and bulbs to diversify and enrich their yearly floral offerings. My grandmother sacrificed valuable garden space to grow another kind of nourishment, flowers for her ancestors. Tradition, brought over from Scotland decades before, demanded that she do so.

If my mother told me this earlier, I wasn’t ready to hear it. Like many folks people of primarily European protestant descent, I have long felt a lack of inherited tradition for honoring those who came before. Yet here was an image I could hold onto, a way my mother’s people mourned and honored their beloved dead. For the remembrance occurs not only on the day families gather to place flowers on the graves of those who have died, but throughout the year as the living save bulbs, plant seeds, water, weed and feed the plants they will offer those who have passed.

Some families we are born into, others we choose. For many, the chosen kinship groups are as important as, if not more than, our actual blood relations. We seek out and form community, living together, sharing resources, creating and resisting. Our chosen families form another type of ancestry. Near my house, under the boughs of a weeping cherry tree, lie the ashes of such an ancestor, Samantha Jane Dorsett.

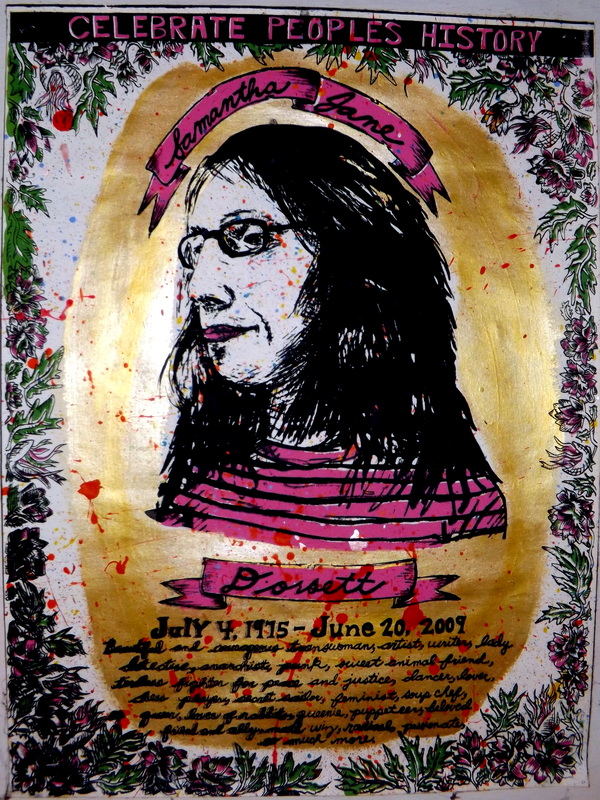

From the poster by Shari Rother:

Celebrate People’s History

Samantha Jane Dorsett

Beautiful and courageous—transwoman, artist, writer, lady detective, anarchist, punk, sweet animal friend, tireless fighter for peace and justice, dancer, lover, chess player, secret sailor, feminist, soup chef, queer, lover of rabbits, queenie, puppeteer, beloved friend and ally, math whiz, radical, passionate, so much more.

Celebrate People’s History

Samantha Jane Dorsett

Beautiful and courageous—transwoman, artist, writer, lady detective, anarchist, punk, sweet animal friend, tireless fighter for peace and justice, dancer, lover, chess player, secret sailor, feminist, soup chef, queer, lover of rabbits, queenie, puppeteer, beloved friend and ally, math whiz, radical, passionate, so much more.

Samantha left us in June of 2009, but her life and work continue to reverberate; generations who never met her know her influence, through the stories, songs and art she left behind, as well as that of the people who have memorialized her in their own work. This year, our apprentices helped create a memorial garden for Samantha around the tree that grows from her ashes. Two of them already knew her story and her legacy. We gathered herbs from around the land to honor her: angelica and yarrow for protection, rose for opening the heart and soothing the pain of grief, mugwort for those who live between worlds and red clover to attract her beloved rabbits. Now and in the spring, I’ll plant bulbs and seeds, carrying on the tradition of the grandmother I never met. Each time I weed or water, each time I contemplate the beauty of the flowers, from the early pink blossoms of the cherry to the deep hues of the gladiolas in late summer, I will honor both their memories.

After landscaping Samantha’s garden, we lit a candle and set off fireworks to celebrate her birthday.

As I write this, I look out onto the spectacular display of yellow, crimson and orange leaves that signifies the coming of winter. The days become shorter, most of the plants die back and it is impossible not to reflect on the cycle of life and death. Autumn compels us to contemplate our own mortality and that of those we love. Many cultures in the northern hemisphere honor those who have passed during this time of transition. This fall, I would like to offer you a tradition, passed down from my grandmother: make a memorial garden. Prepare a garden bed, plant some bulbs and fall seeds. Plant more seeds and starts in the spring. There are many ways to plan a garden. Choose flowers your loved ones admired. Pick different flowers to bloom sequentially through the year. Or choose herbs for their medicine or symbolism. As you tend this garden, think of your loved ones that are gone, be they related to you by blood or friendship. Tend their memories as you tend the plants. From sorrow, foster beauty and comfort. From death, reconnect with life. As you tend to the roots of the plants, so you tend to your own.

with love,

Janet

What a gift – you and this message. It’s helping a dear friend grieve his mother (I stumbled upon your page today doing a whole other search). I’m inspired to share these beautiful seeds of yours. Beauty is such a powerful healing medicine for us to honor our ancestors and planet.

LikeLike